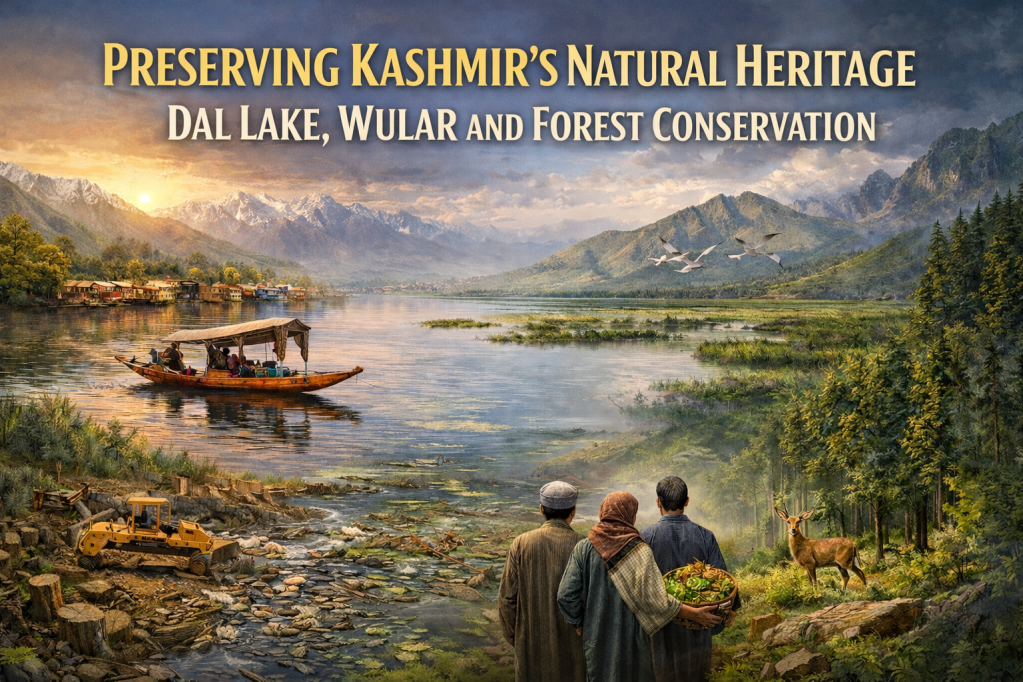

Kashmir has long been described as paradise on earth, a phrase that risks sounding worn out until one stand at the edge of Dal Lake at dawn or watches the vast expanse of Wular Lake shimmer under a changing sky. These landscapes are not merely scenic backdrops; they are living systems that have shaped Kashmiri culture, livelihoods, memory and identity for centuries. Yet today, this natural heritage stands at a crossroads. Environmental degradation, unchecked urbanization, climate change and governance failures are steadily eroding the ecological foundations of the Valley. The fate of Dal Lake, Wular Lake and Kashmir’s forests reflects a larger struggle between preservation and neglect, between short-term convenience and long-term survival.

Dal Lake is perhaps the most iconic symbol of Kashmir, woven deeply into its cultural and economic life. For generations, it has been home to fishing communities, vegetable growers and shikara operators whose lives rise and fall with the lake’s health. Floating gardens or radhs, once exemplified a delicate harmony between human activity and nature. Today, that harmony is increasingly fragile. Pollution from untreated sewage, solid waste and encroachments has drastically altered the lake’s ecosystem. What was once crystal clear water has turned murky in many stretches, choked by weeds and algae fed by nutrient overload. Houseboats, once symbols of elegance and heritage, now often lack proper waste management systems, adding to the ecological burden.

The tragedy of Dal Lake is not merely environmental; it is human. Families that have lived on the lake for decades now face displacement in the name of conservation, often without adequate rehabilitation. Conservation efforts, while necessary, have frequently been executed without empathy, consultation or livelihood planning. This has created mistrust between authorities and lake dwellers, weakening the very cooperation essential for ecological restoration. True preservation cannot be achieved by removing people alone; it must involve them as custodians rather than obstacles.

Wular Lake, Asia’s largest freshwater lake, presents a different but equally troubling story. Unlike Dal, Wular does not enjoy the same visibility or tourist attention and perhaps for that reason its degradation has unfolded more quietly. Historically, Wular acted as a natural flood basin for the Jhelum River, absorbing excess water during heavy rainfall and snowmelt. Its wetlands supported migratory birds, fisheries and agriculture, forming a vital ecological buffer for north Kashmir. Over the years, however, large-scale encroachments, conversion of wetlands into agricultural land, excessive willow plantations and siltation from upstream deforestation have shrunk the lake dramatically.

The consequences of Wular’s decline extend far beyond its shores. Reduced water-holding capacity has intensified flooding downstream, while the loss of wetlands has disrupted biodiversity and livelihoods. Fishermen who once depended on abundant catches now struggle to sustain their families. Seasonal migrants who followed bird migration cycles have disappeared from the area, taking with them cultural practices that once enriched the region’s ecological diversity. Wular’s decline is a stark reminder that ecosystems do not fail in isolation; their collapse reverberates across landscapes and communities.

Equally critical to Kashmir’s environmental future are its forests, which cover large swathes of the Valley’s mountains and foothills. These forests are more than collections of trees; they regulate climate, prevent soil erosion, recharge groundwater and provide livelihoods through timber, firewood, medicinal plants and grazing. They also act as Kashmir’s first line of defence against natural disasters. Yet deforestation, both legal and illegal, has taken a heavy toll. Development projects, road construction, unplanned tourism infrastructure and timber smuggling have steadily fragmented forest cover.

Climate change has further exacerbated the crisis. Erratic snowfall patterns, receding glaciers and increased frequency of extreme weather events are placing immense stress on already weakened ecosystems. Forest degradation accelerates these impacts, making landslides more frequent and floods more destructive. The devastating floods of 2014 served as a painful reminder of what happens when natural buffers are compromised. While multiple factors contributed to that disaster, the loss of wetlands and forests played a significant role in amplifying its impact.

What unites the challenges facing Dal Lake, Wular Lake and Kashmir’s forests is not just environmental mismanagement but a deeper governance crisis. Conservation policies often exist on paper but falter in implementation. Jurisdictional overlaps between departments, lack of scientific planning and short political cycles have undermined sustained ecological action. Environmental protection is frequently treated as a secondary concern, easily sacrificed to infrastructure expansion or commercial interests. When conservation does occur, it is often reactive rather than preventive, addressing visible damage instead of underlying causes.

Yet, amid this bleak picture, there are reasons for cautious hope. Community-led initiatives, though limited in scale, demonstrate that restoration is possible when people are placed at the center of conservation. In pockets around Dal Lake, efforts to revive traditional waste management practices and reduce chemical use in floating gardens have shown modest improvements.

Around Wular, wetland restoration projects aimed at desiltation and removal of invasive species have begun to reclaim lost water bodies, though progress remains slow. In forest areas, joint forest management committees have empowered local communities to protect nearby woodlands, aligning ecological health with livelihood security.

Tourism, often seen as a threat, can also become a tool for conservation if managed responsibly. Kashmir’s economy relies heavily on its natural beauty, yet mass tourism has strained fragile ecosystems. Sustainable tourism models that limit footfall, regulate construction and reinvest revenue into conservation could transform visitors into stakeholders rather than consumers. Educating tourists about ecological sensitivity, waste disposal and local traditions can foster respect for landscapes that are too often treated as disposable attractions.

Education and awareness within Kashmir are equally crucial. Environmental consciousness must move beyond occasional clean-up drives to become part of everyday civic responsibility. Schools, universities, religious institutions and media all have a role to play in reshaping how Kashmiris perceive their relationship with nature. The Valley’s cultural traditions already contain deep reverence for land and water; reviving these values in modern contexts could strengthen conservation efforts in ways that laws alone cannot.

Ultimately, preserving Kashmir’s natural heritage is not a choice but a necessity. Dal Lake cannot survive as a postcard image divorced from ecological reality. Wular Lake cannot protect the Valley from floods if it continues to shrink. Forests cannot shield communities from climate extremes if they are treated as expendable resources. Environmental degradation threatens not only biodiversity but also food security, public health, economic stability and social harmony.

The future of Kashmir will be shaped as much by its ecological decisions as by its political ones. Conservation must move beyond symbolic gestures and fragmented interventions toward a holistic, long-term vision that integrates science, community participation and accountable governance. This requires political will, sustained funding, and above all, the recognition that development and environmental protection are not opposing goals but interdependent ones. Kashmir’s lakes and forests have given generously to its people for centuries, absorbing floods, feeding families and offering solace in times of turmoil. Preserving them is an act of responsibility to future generations, a commitment to ensuring that the Valley remains not just beautiful, but livable. The question is no longer whether Kashmir can afford conse