Farming in the mountains is a study in resilience. Steep slopes, thin soils, short growing seasons and fragile ecosystems demand methods that conserve water and nutrients while protecting landscapes from erosion. Around the world, farmers have shaped hillsides into terraced steps, diversified their fields to hedge against climate swings and stored harvests to outlast long winters. In India’s Himalayan arc, the Gurez Valley of Jammu and Kashmir offers a vivid example of how sustainability is not a trendy add-on – it’s the only way mountain agriculture endures.

Sustainable farming in highlands follows three interlocking principles: Unchecked rain can strip soil on slopes within a few seasons. Terracing converts gradients into gentle steps that slow runoff, trap sediment and increase infiltration. Where terraces aren’t feasible, contour bunds, vegetative strips and stone lines stabilise soil and create micro-catchments. Mulching with crop residues and farmyard manure protects the surface, keeps moisture and feeds soil life. Mountain weather is fickle late frosts, cloudbursts and sudden droughts are common. Mixed cropping and short-duration, hardy varieties reduce risk. Integrating livestock closes nutrient loops: crop residues become fodder and manure returns to fields, boosting organic matter and water-holding capacity. Simple protected cultivation – low tunnels and poly houses extends seasons, shelters seedlings and buffers hail or wind.

Sustainability only sticks when it pays. Niche, high-value mountain products like heritage spices, pulses, seed potatoes and temperate fruits can lift incomes if backed by storage, processing and market access. Community institutions, cooperatives, local Krishi Vigyan Kendras and research stations translate techniques into practice and help farmers capture value.

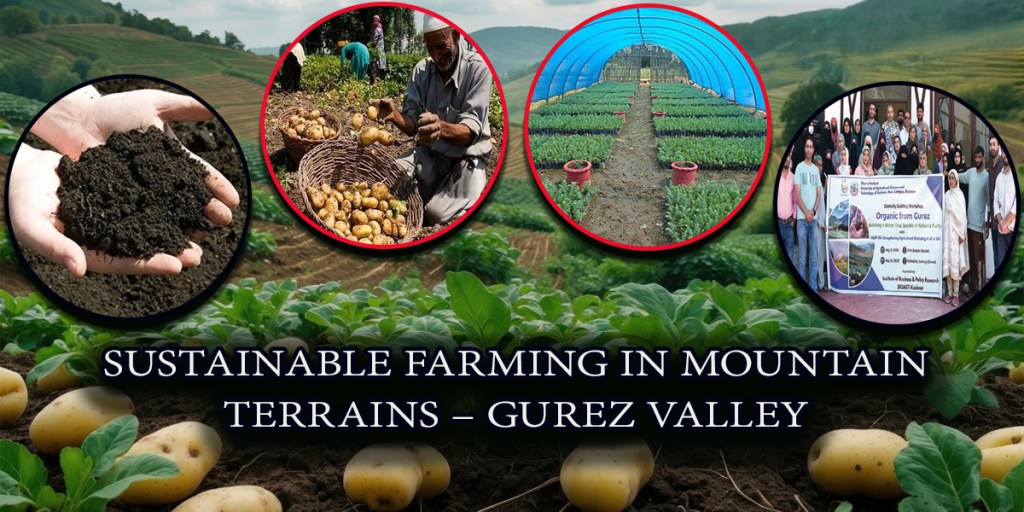

Set around 8,000 feet, Gurez Valley is snowbound for months each year, which forces farmers to be both frugal and inventive. Potatoes are a mainstay here recent reports estimate production in the valley at roughly 15,000 tonnes annually, a remarkable feat given the short summer and challenging terrain. Farmers traditionally store their harvest in earth pits and insulated structures to survive long winters an ancient, low-energy method that reduces spoilage and stabilises the food supply. Beyond potatoes, Gurez fields support maize, wheat, peas and rajma, often in mixed or sequential systems to make the most of the 100 –120 frost-free days. Extension efforts have also introduced improved wheat and maize varieties tailored to the valley’s three sub-zones Bagtore, Dawar and Tulail aligning seed choice with altitude and microclimate. One of Gurez’s most distinctive assets is kala zeera, a slow-growing heritage spice that thrives in high, cool valleys. It’s well-suited to low-input, organic conditions and commands premium prices, offering a pathway to conservation-led incomes for remote communities.

Gurezi farmers rely on farmyard manure and compost rather than synthetic inputs, partly because of tradition and partly because winter logistics make agrochemical supply difficult. This organic orientation keeps soils spongy, supports earthworms and microbes and helps fields retain scarce moisture during summer dry spells. It also dovetails with the valley’s market narrative of “pure, mountain-grown” produce. Local commentary and university outreach consistently emphasise keeping Gurez pesticide-free and building on its organic identity with crops like potatoes, pulses and black cumin. Farmers use terracing and contour-aligned plots on cultivable hillsides to slow water and reduce soil loss –a cornerstone of Himalayan farming. Where new terraces are impractical, grassed edges and stone bunds stabilise beds and provide cut-and-carry fodder. These are standard, proven measures for India’s hilly regions, including the Kashmir highlands. Because Gurez spans multiple altitude bands, the valley staggers sowing and variety choices. In the short summer pulses, maise and potatoes dominate, with some oats and temperate fruit trees in lower and middle zones an agroecological mosaic that spreads risk and sources fodder. Winter sees a near-complete halt in field activity, so post-harvest handling and storage are critical to food security and income smoothing.

Krishi Vigyan Kendra-Gurez and partner institutions have been distributing quality planting material and training farmers on protected cultivation to extend the season and improve the survival of seedlings. Such micro-infrastructure is transformative in high valleys: a small poly house can mean reliable nurseries, earlier market entry and better prices. From seed potato multiplication programs to renewed interest in traditional storage pits, the valley invests in upstream and downstream resilience. Seed multiplication suited to local conditions reduces dependence on distant suppliers, while low-energy storage keeps quality and waste low. Together, they anchor a circular, climate-smart system. Mountain climates are intensifying. Gurez has recently faced notable drought conditions, a stark reminder that even cool, high valleys are not immune to water stress. Diversifying beyond a single staple, selecting short-duration varieties and reviving water harvesting all help. Community weather advisories and crop insurance can add a financial safety net to biophysical measures on the farm. A practical sustainability checklist for mountain regions.

Build soil capital: Compost, green manures and residue mulching every season. Farm the contour: Terraces or contour strips; maintain grassed edges and stone bunds. Diversify by altitude: Match varieties and sowing windows to elevation zones; mix cereals, pulses and tubers. Close the loop with livestock: Integrate stall-fed animals, return manure to fields and grow fodder on terrace risers. Invest in protected cultivation: Simple low tunnels or poly houses for nurseries and off-season vegetables. Secure the harvest: Adopt low-energy storage, community grain banks and seed cooperatives. Lean into niche crops: Heritage spices like kala zeera, seed potatoes and temperate fruits create premium value with modest land. Organise for markets: Collaborate with Krishi Vigyan Kendras and local institutions to aggregate produce, access planting material, and reach buyers. Sustainable farming in mountain terrain is neither novelty nor nostalgia – it’s the living wisdom of communities like those in Gurez. Mountain farmers can turn their constraints into comparative advantages by conserving soil and water, diversifying crops and incomes and strengthening local institutions. When a high valley stores potato in earth’s cool embrace, tends spice crops that only altitudes can perfect and nurtures soils with organic matter, it isn’t just coping – crafting a resilient food system that lowlands would do well to learn from.