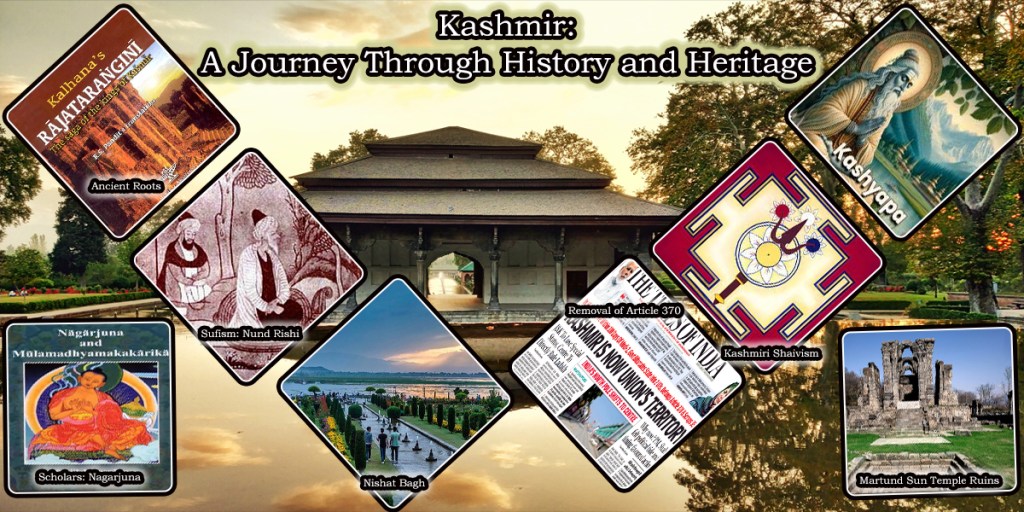

Kashmir, often described as “Paradise on Earth”, is one of the most beautiful and historically significant regions of South Asia. Surrounded by the towering Himalayas, snow-clad mountains, rivers and lush valleys, the region has fascinated poets, kings, and travelers for centuries. But beyond its natural beauty lies a long and layered history shaped by religion, culture and politics. The earliest references to Kashmir appear in ancient texts like the Mahabharata and the Rajatarangini, a 12th-century Sanskrit chronicle written by Kalhana. According to legend, Kashmir was once a vast lake, drained by the sage Kashyapa, from whom the region is believed to derive its name. Archaeological findings also suggest that Kashmir was an important center of early settlement and civilization.

By the 3rd century BCE, Kashmir became a part of the Mauryan Empire under Emperor Ashoka. He introduced Buddhism to the valley, which flourished here for centuries. Kashmir became an intellectual hub for Buddhist scholars and monks and the region played a role in spreading Buddhism to Central Asia and Tibet. Ashoka is also credited with building cities and stupas in the valley. Later, during the Kushan rule 1st–3rd century, Kashmir saw cultural exchanges with Central Asia. The famous Buddhist philosopher Nagarjuna is believed to have taught in Kashmir during this period. Hinduism also remained deeply rooted and over time, Kashmir developed as a land of spiritual synthesis between Hindu and Buddhist traditions.

Between the 7th and 12th centuries, Kashmir was ruled by Hindu dynasties such as the Karkotas and the Utpala kings. Lalitaditya Muktapida, a powerful king of the Karkota dynasty, expanded his kingdom beyond Kashmir and built magnificent temples, including the Martand Sun Temple, whose ruins still stand today. This was also the golden age of Kashmiri art, literature and philosophy. The valley became a renowned center of learning, especially in Sanskrit studies. The Kashmiri Shaivism school of Hindu philosophy, which emphasized the unity of the self with the divine, emerged here and attracted scholars from across India.

Kalhana’s Rajatarangini remains one of the most important historical texts about Kashmir. It records the reigns of kings, dynasties and the socio-political conditions of the region up to his time, making it a vital source for historians. In the 14th century, a major transformation occurred with the arrival of Islam in Kashmir. The new faith spread gradually, not by force, but largely through the influence of Sufi saints such as Hazrat Bulbul Shah and Sheikh Noor-ud-Din Noorani also known as Nund Rishi. Their teachings of peace, harmony and brotherhood resonated with the people, leading to the widespread acceptance of Islam while preserving Kashmir’s pluralistic traditions.

In 1339, Shah Mir became the first Muslim ruler of Kashmir, founding the Shah Mir dynasty. His successors consolidated Islamic rule in the valley and Kashmir developed a distinct culture blending Persian, Central Asian and local traditions. This era saw the construction of mosques, khanqahs and madrasas, alongside the continued existence of Hindu and Buddhist practices. By the 16th century, Kashmir caught the attention of the mighty Mughals. In 1586, Emperor Akbar annexed Kashmir into the Mughal Empire. The Mughal emperors, especially Jahangir were enamored by the valley’s beauty. Jahangir famously said, “If there is paradise on earth, it is this, it is this, it is this.” During this period, Mughal gardens such as Shalimar Bagh and Nishat Bagh were built, which still remain iconic landmarks.

After the decline of Mughal power, Kashmir fell under Afghan rule in 1752 when Ahmad Shah Durrani’s forces took control. The Afghans ruled harshly and the population suffered under heavy taxation and repression. Their rule lasted for about 67 years. In 1819, the Sikh Empire under Maharaja Ranjit Singh defeated the Afghans and annexed Kashmir. For about 27 years, the Sikhs ruled the valley. After Ranjit Singh’s death, the British defeated the Sikhs in the First Anglo-Sikh War 1846. As part of the Treaty of Amritsar, the British sold Kashmir to Gulab Singh, the Dogra ruler of Jammu, for 7.5 million rupees. Thus began the Dogra dynasty’s rule over Kashmir. Under Dogra rule 1846–1947, Kashmir became a princely state of British India. The Dogras maintained tight control and the predominantly Muslim population of Kashmir faced economic and social hardships, while the ruling elite were largely Hindu. This disparity sowed the seeds of future discontent.

At the time of India’s independence in 1947, Kashmir was a princely state with the option to join either India or Pakistan. Maharaja Hari Singh, the Dogra ruler, initially wanted to remain independent. However, in October 1947, tribesmen from Pakistan invaded Kashmir, leading the Maharaja to seek India’s help. In return, he signed the Instrument of Accession, making Kashmir part of India.

This sparked the first war between India and Pakistan in 1947 – 48, after which the region was divided. India retained control over Jammu, the Kashmir Valley and Ladakh, while Pakistan held what it calls “Azad Kashmir” and Gilgit-Baltistan. The issue was later taken to the United Nations, which called for a plebiscite, but it was never held due to differing conditions set by both sides.

Since 1947, Kashmir has remained a sensitive and contested region. India and Pakistan fought additional wars in 1965 and 1971, with Kashmir as a central issue. The region has witnessed insurgency, political unrest and cross-border tensions since the late 20th century. In August 2019, the Government of India revoked Article 370 of its Constitution, which had granted special status to Jammu and Kashmir. This move was historic and controversial, reshaping the region’s political landscape.

The history of Kashmir is a tale of beauty and conflict of cultural richness and political struggles. From ancient Hindu and Buddhist traditions to the arrival of Islam, from Mughal gardens to Dogra rule and from the partition of 1947 to the present day, Kashmir’s journey has been complex. It continues to be a land of immense cultural heritage and natural splendor, even as its future remains a subject of global interest and debate.