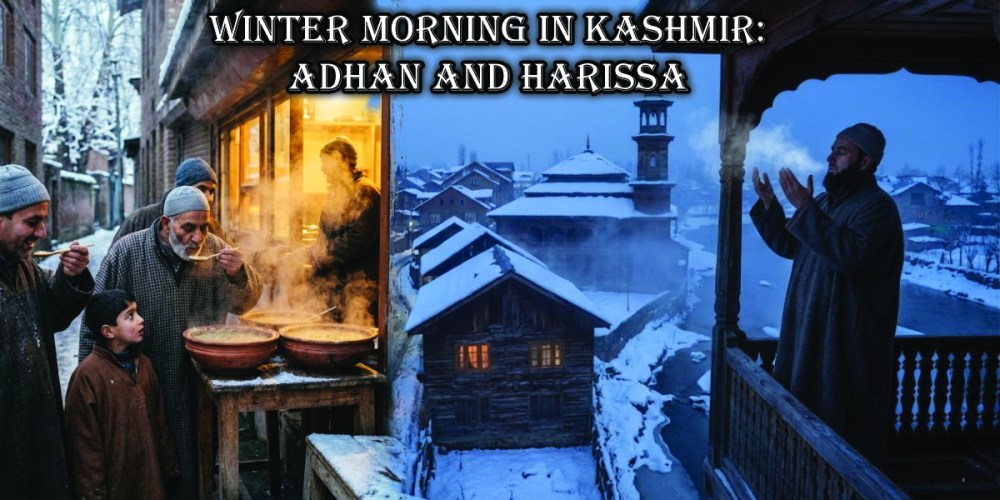

In Kashmir, winter mornings begin long before the sun rises. The Valley lies wrapped in silence, streets still asleep, frost settling gently on rooftops. Then, cutting through the cold air, comes a sound that every Kashmiri knows by heart — the morning Adhan. It echoes across neighbourhoods, calm yet commanding, reminding people that another day has begun. For many, this moment marks more than prayer time. It signals the arrival of one of winter’s most cherished rituals — piping hot Harissa.

This pairing of the early morning Adhan and a bowl of steaming Harissa is not accidental. It is tradition shaped by climate, labour, faith and memory. In the harsh Kashmiri winter, when temperatures drop below freezing and the body craves warmth from within, Harissa becomes more than food. It becomes fuel, comfort and continuity.

Harissa is not prepared in haste. It is slow-cooked overnight in large copper vessels known locally as deighs. The process begins late in the evening, long after most households have settled in. Meat, rice, spices and bone marrow are left to simmer gently over low heat, stirred continuously for hours. This slow preparation is essential. Harissa is not meant to rush. Like winter itself, it demands patience.

By the time the morning Adhan resonates through the cold air, Harissa is ready. Vendors begin opening their shops even before dawn. Steam rises from massive pots, fogging up windows and drawing people in. Long queues form quietly. There is no noise, no urgency — just the shared understanding that this moment belongs to everyone. A nod here, a soft salaam there. Kashmir wakes up gently.

For many Kashmiris, winter mornings are unimaginable without this routine. Laborers heading to work, shopkeepers opening shutters, students preparing for exams, elders stepping out for fresh air — all pause briefly for Harissa. It is eaten standing outside shops, sitting on low stools, or carried home carefully wrapped to be shared with family. The first spoonful warms the chest instantly. In Kashmiri homes, it is often said that Harissa “andar tak garm karti hai.”

Journalistically, Harissa reflects how food adapts to environment. Kashmir’s winters are long and physically demanding. Historically, people needed high-energy meals early in the day to sustain themselves. Harissa, rich in protein and slow-release carbohydrates, fulfills this need perfectly. It is heavy, nourishing and meant to be eaten slowly. This is why it is almost exclusively a winter and morning dish. Eating it later in the day feels unnatural to most Kashmiris.

There is also a spiritual rhythm tied to this tradition. The morning Adhan sets the tone — discipline, reflection and calm. Harissa follows as a worldly reward, grounding the body after the call to prayer. Faith and food coexist seamlessly here, not competing but complementing each other. For many elders, this combination represents balance — ibadat followed by sustenance.

Harissa shops themselves are cultural spaces. Most are modest, unchanged for decades. The men preparing it are specialists, often inheriting the craft from their fathers. They know the exact consistency by instinct, judging readiness not by clocks but by texture and aroma. A slight change in stirring or heat can ruin hours of work. This knowledge is not written down. It lives in hands and memory.

Despite modernization, Harissa has resisted commercialization. It is rarely found outside Kashmir in its authentic form. Attempts to replicate it often miss its essence — the slow cooking, the winter air, the early hour. Even within Kashmir, people are particular. Everyone has a preferred Harissa spot. Debates over which vendor makes the best Harissa are common and deeply personal.

For Kashmiris living outside the Valley, Harissa becomes a powerful symbol of home. Winter mornings abroad feel incomplete without the familiar steam and smell. Some try to recreate it in kitchens far away, but most agree — it tastes different without the cold air, the Adhan and the shared silence of a Kashmiri morning.

Health-wise, Harissa is both praised and approached with caution. Its richness makes it ideal for cold weather but unsuitable for excess. Kashmiris know this instinctively. Harissa is seasonal, not indulgent. It is respected, not overused. Like many traditional foods, moderation is part of the wisdom.

As winters change and lifestyles evolve, some fear that such traditions may fade. Yet every winter, Harissa returns. Young people still line up at dawn. Old shops still open before sunrise. The ritual survives because it meets both physical and emotional needs. It offers warmth, familiarity and a sense of belonging in a season that can otherwise feel isolating.

In the end, the tradition of morning Adhan and piping hot Harissa is not about nostalgia alone. It is about continuity. It shows how Kashmir has learned to live with winter, not fight it. It reminds people that some comforts do not need reinvention — only preservation.

As long as winters descend upon the Valley, the Adhan will echo through frozen streets and Harissa will steam in waiting bowls. Together, they will continue to mark the beginning of Kashmiri mornings — quiet, nourishing and deeply rooted.