Kashmir has always lived with the quiet authority of mountains. The Himalayas frame everyday life not only as scenery but as destiny—shaping climate, culture, mobility and risk. Beneath these ranges, unseen and often unspoken, lie fault lines that have carried memory across generations: the tremor felt during a winter night, the crack along an old wall, the sudden silence that follows a shaking floor. Earthquakes here are not daily events but they are never abstract. They exist as a background truth, woven into the Valley’s long relationship with uncertainty.

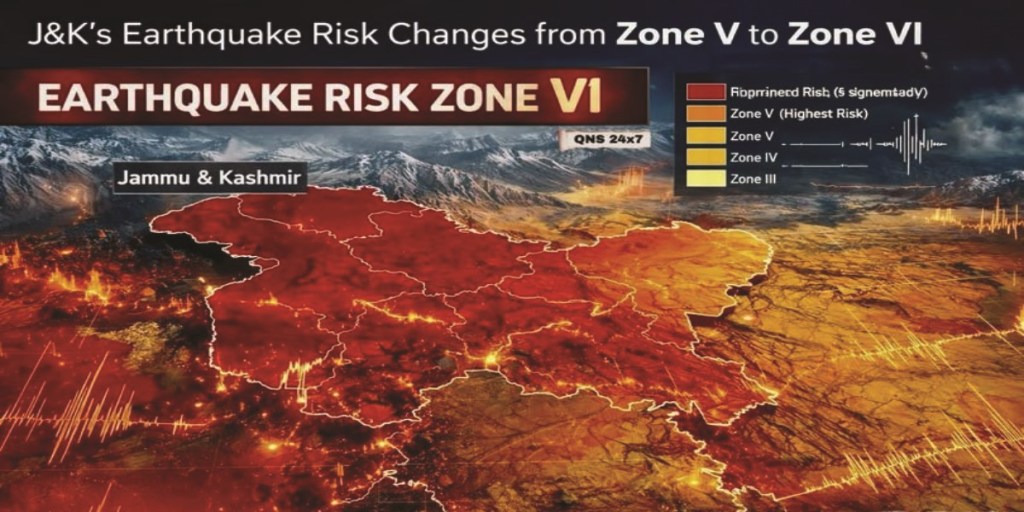

It is against this lived backdrop that the recent reclassification of Jammu & Kashmir’s seismic status—from Zone V to the newly defined Zone VI—must be understood. The change has drawn attention, concern and questions. What has changed? Why now? And what does it mean for everyday life in Kashmir? For decades, much of Jammu & Kashmir was already categorised under Seismic Zone V, the highest risk level in India’s earlier zoning system. The shift to Zone VI does not imply that danger has suddenly appeared. Rather, it reflects an evolution in scientific understanding and assessment methods.

This reclassification emerges from updated seismic hazard frameworks that rely on improved data, advanced modelling and a deeper understanding of Himalayan tectonics. Scientists now use probabilistic seismic hazard assessments that go beyond historical earthquakes to include fault behaviour, strain accumulation and expected ground motion. Zone VI represents an acknowledgement that the Himalayan belt—including J&K and Ladakh—faces a level of seismic hazard that warrants a distinct, highest-risk category. Importantly, this is not a reaction to a single recent study or event. It is the outcome of years of accumulated research. Better instruments, better models and better mapping have led to a more precise—if sobering—classification. The science has sharpened; the ground beneath us has not suddenly changed.

Seismic zones are not predictions of when an earthquake will occur. They are risk categories that estimate how strong the ground may shake when earthquakes do happen. These zones are defined by factors such as proximity to active fault lines, the rate of tectonic plate movement, geological structure and expected peak ground acceleration—the intensity of shaking likely to be experienced. One way to understand this is to think of pressure building under snow-laden slopes in winter. The slope itself may appear stable for weeks, but the pressure accumulates silently. Earthquake zoning maps where such pressure exists beneath the earth’s surface and how violently it may be released.

Zone VI differs from earlier classifications by recognising that parts of the Himalayas can experience stronger ground motion than previously accounted for. It is a refinement, not a rupture, in how risk is understood. A recent study has added another layer to this understanding by examining what is happening deep beneath the Tibetan Plateau. Researchers suggest that the Indian tectonic plate, as it continues to push northward beneath Eurasia, is experiencing a form of deep tearing or separation at great depths.

This process is neither sudden nor shallow. It occurs tens to hundreds of kilometres below the surface and unfolds over geological timescales measured in millions of years. It does not mean that the land will split apart, nor does it signal an imminent catastrophe.

However, such deep structural changes influence how stress is distributed across the Himalayan region. Over time, they can affect where and how energy accumulates along faults closer to the surface. For regions like Kashmir—situated along one of the world’s most active collision zones—this reinforces the understanding that seismic risk is structural and long-term, not episodic or accidental.

The implications of Zone VI are not theoretical. They touch homes, schools, hospitals and roads. Housing remains the most immediate concern. Traditional timber-and-brick homes, which once showed surprising resilience due to flexibility, now coexist with reinforced concrete structures of varying quality. Informal construction—often driven by necessity rather than neglect—has expanded in towns and villages alike. Many such buildings were not designed with seismic detailing in mind.

Public infrastructure presents a mixed picture. While newer hospitals and institutions may incorporate earthquake-resistant designs, countless older schools, health centres and administrative buildings remain vulnerable. In remote, snow-bound areas, access constraints compound the risk: response time after a major quake could be measured not in hours, but in days. For ordinary families, the challenge lies in navigating between anxiety and action. Awareness of risk exists, but practical preparedness—safe construction, retrofitting, emergency planning—lags behind.

Rapid urban growth has intensified these vulnerabilities. Srinagar’s expansion into wetlands and lake margins, construction on unstable slopes around Jammu and densification without proportional planning have increased exposure. Building codes exist but enforcement is uneven. Illegal constructions and encroachments are often addressed only after irreversible damage has been done.

Earthquakes do not discriminate between legal and illegal structures. When the ground shakes, it tests the weakest decisions made over decades.The shift to Zone VI should not be read as a warning bell for panic. It is a policy and planning signal—an invitation to act with foresight.

Earthquake-resistant construction is not an exotic technology; it is a set of principles that can be integrated into local building practices. Retrofitting older buildings, prioritising schools and hospitals, conducting regular drills and investing in public awareness can significantly reduce loss.

Governance has a central role here. Scientific knowledge must translate into building approvals, urban planning decisions and community-level training. Preparedness is not a one-time exercise but a continuous process.

Kashmir’s history is marked by adaptation—to weather, terrain and circumstance. The mountains have taught patience; winters have taught planning. The new seismic classification should be approached in the same spirit.

Zone VI is not a prophecy of disaster. It is a clearer mirror held up by science, asking society to build with care and live with awareness. Resilience, after all, has never been foreign to Kashmir. What is required now is to align that inherited resilience with modern knowledge—quietly, steadily and without fear.

Very interesting and valuable information and very well articulated in the article.

LikeLike